By P.K.Balachandran/Daily News

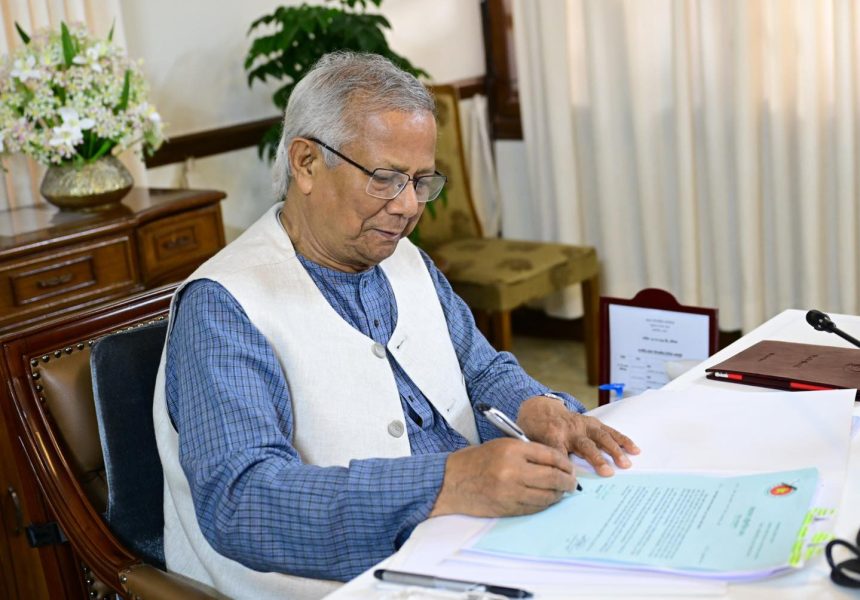

Colombo, June 10-In his address to the nation on the eve of Eid, late last week, Prof. Muhammad Yunus, the head of the Interim Government of Bangladesh, announced that parliamentary elections will take place in the first half of April 2026. The last parliament, elected in January 2024, had been unceremoniously dissolved in August as a result of a month-long violent mass student movement against the then Prime Minister Sheikh Hasina.

The Interim Government, which took office in August 2024, promised to hold elections to a new parliament at the earliest but only after completing necessary constitutional and administrative reforms. The Interim Government set up committees to formulate reforms in multiple sectors.

Yunus’ Justification

Justifying his decision to hold elections in April 2026 and not in December 2025 as demanded by more than 10 political parties, Yunus said that he believed that by the next Eid-ul-Fitr, Bangladesh will be able to reach “an acceptable point on reform and justice.”

He urged people “to obtain specific commitments” from all political parties and candidates that they will “approve without any change, in the very first session of the next parliament, the reforms on which consensus has been reached.”

Yunus also promised that he would see that the elections had “ full participation” and that the polls would be the most free and fair in the history of Bangladesh.

Poor Record

Months rolled by since Yunus took over, but there were no signs of any reforms., There was no clue as to what the committees he had set up were doing. The Interim Government was also failing in its primary duty to “govern” the country. Law and order had broken down and unrest was rampant. Systems were not allowed to function by agitations by one section of society or the other.

Meanwhile, political parties were wondering if Yunus and his Advisory Committee, comprising mostly non-politicians, were wanting to remain in power without a mandate, indefinitely.

An established political party like the Bangladesh National Party (BNP) strongly expressed the view that reforms could be fashioned only by an elected parliament, not an Interim Government hurriedly set up during a period of political turmoil. Yunus, on the other hand, had urged people “to obtain specific commitments” from all political parties and candidates that they will “approve without any change, in the very first session of the next parliament.”

Strictly speaking, Yunus and his fellow Advisors have no mandate, constitutional or electoral. Therefore, the BNP made a strong case for elections to be held by December 2025 and demanded that the task of reforming the Bangladeshi system be left to the freshly elected parliament. Left parties were also of the same view.

While crime of all kinds was rampant, the Interim Government was only concentrating on arresting and jailing its opponents especially those who had anything to do with Sheikh Hasina’s party, the Awami League.

Yunus promised “full participation” in the elections” but banned the Awami League. To his advantage, most parties, including the BNP, supported the ban. However, according to neutral observers, the Awami League still has a committed supporters who admire Sheikh Mujibur Rahman and the independence movement against Pakistan he led.

The Army chief, Gen.Waker uz Zaman, also urged Yunus to hold elections before December 2025 so that reforms could be carried out in a democratic manner. He warned that the law and order could not be ensured in the absence of an elected government.

April Unsuitable

Bangladesh Nationalist Party Secretary General Mirza Fakhrul Islam Alamgir stated that April is not an appropriate time for national elections.

“April experiences extreme heat, potential storms and rains, and public examinations right after Ramadan. Holding elections during this period isn’t practical. It doesn’t appear that this was properly considered.”

“Running campaigns during Ramadan will also be challenging. Our Standing Committee already deliberated on this matter. We believe elections should be held in December – that would be most suitable for the country,” Alamgir said.

The Left Democratic Alliance (LDA) also demanded elections by December. The LDA termed Yunus’ speech as “disconnected from the public sentiment” and saw in it “Yunus’ ambition to continue in power for as long as he could.” Yunus had failed to address critical issues faced by working-class people, such as unpaid wages and bonuses before Eid. The LDA said that holding elections during Ramadan, academic exams, the rice harvest, and the monsoon is neither practical nor acceptable. It further stated that by announcing elections in April while ignoring the views of most political parties and citizens, Dr. Yunus had ceased to be consultative

“The delay in elections is clearly designed to serve the interests of a particular party or group and risks pushing the country deeper into crisis under imperialist and hegemonic influence,” the LDA said, alleging that the Yunus government of being under the influence of the US.

NCP and Jamaat

However, the National Citizen Party, the newly formed political party comprising students who participated in the July-August 2024 uprising against Sheikh Hasina, has been pushing for the election to be held after reforms are completed. They have pitched for July 2026.

The Jamaat-e-Islami intially had a similar stance to the NCP. The party then said the election can take place in February, before Ramadan. Last week, top Jamaat leaders said the elections can take place between December 2025 and April 2025.

Writing in the Press Express on May 31, Sheikh Mohammad Fauzul Mubin recalls that Dr. Yunus, having secured the position of Chief Advisor through an “opaque and politically contentious process” following the ouster of the Awami League government, now presides over a regime that lacks electoral legitimacy.

“Instead of steering the country toward a timely democratic transition, his government appears increasingly committed to maintaining control without the mandate of the people. Central to this strategy has been the establishment and backing of a blossoming political party, comprised largely of his young student apprentices —many of whom have already been implicated in corruption of millions of dollars and administrative misconduct. This political formation, viewed by many as a proxy for Yunus’s personal ambitions, has only added to the growing distrust surrounding his leadership,” Mubin wrote.

Internal Challenge

Yunus is not unchallenged from within the system, Mubin contends. Only Yunus and his inner circle appear opposed to an immediate election. As BNP Standing Committee member Mirza Abbas pointedly noted, “The only person who doesn’t want elections is Professor Yunus.”

One of the most significant reasons behind Yunus’s reluctance to facilitate elections lies in the interim regime’s declining popularity and increasing allegations of corruption, Mubin contended. According to him. the Anti-Corruption Commission (ACC) has launched investigations into several high-ranking officials close to the regime, including a former Assistant Private Secretary (APS), personal officers of advisers, and Gazi Sahlahuddin Tanvir, a former joint secretary of the Yunus-backed National Citizen Party (NCP).

“These inquiries suggest that deep-rooted corruption has severely damaged the credibility of the interim government. Holding free and fair elections could open the door to accountability, both political and legal. Hence, avoiding elections becomes a matter of political survival,” Mubin argues.

Democracy vs Technocracy

Ultimately, Yunus’s endgame appears to be the replacement of democratic mandates with technocratic governance, Mubin says.

“By sidelining political parties, delaying elections, and empowering unelected legal, bureaucratic, and civil society actors, Yunus is attempting to usher in a political order where decisions are made in conference rooms rather than ballot boxes. This governance model is attractive to a certain class of international actors, particularly Western human rights groups and global finance institutions, which value stability and elite consensus over messy electoral politics.”

“But for Bangladeshis, who have fought long and hard for democratic self-determination, this model reeks of paternalism and neo-colonial influence,” Mubin points out.

END